Variety, cultivar, landrace, heirloom: Definitions

I am often asked what is the difference between a variety, a cultivar, a landrace or an heirloom. I can see in various forum or websites a lot of opinions and some laudable efforts to explain with precision the definition of these terms. However, it is rarely accurate. I try here to give not an opinion but precise and sourced definitions. For the record, I am a geneticist / breeder by education. I am grateful to Dr Aaron Davis from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, whose research background is taxonomy and systematics, for eye-opening discussions.

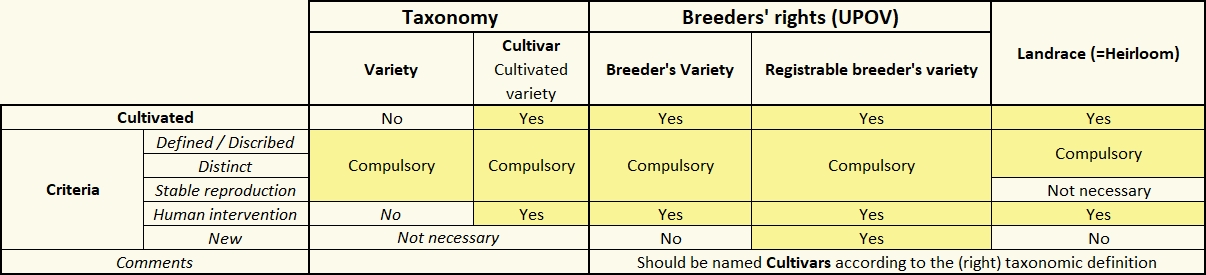

As we will see, the confusion around the meaning of ‘variety’ is stemming from the superposition of a legal approach used to protect breeders’ rights to the original plant taxonomic approach. Even if my background is more on genetics and breeding, I must say breeders could be largely responsible for the confusion.

Short version

The term variety has been clearly defined by taxonomists as a taxonomic rank within species, and for exclusive use for wild plants. It is defined upon botanical characteristics that have been shaped by nature. Taxonomists introduced the term ‘cultivar’ (short for cultivated variety) to acknowledge the fact that some plants are cultivated and/or shaped by man.

When breeders (long after the definition of variety and cultivar by taxonomists) decided to produce the UPOV international framework governing legal aspects of cultivated varieties, they unfortunately used the word ‘variety’, instead of the correct word ‘cultivar’ or cultivated varieties.

Because of the power and reach of breeders and breeding companies, the word ‘variety’ is now widely used in the sense of ‘cultivar’. However, the correct term is ‘cultivar’.

When the term ‘variety’ needs to be used in its true original taxonomic sense, the best approach is to clearly state that it is a botanical variety, at least in narratives concerning coffee.

First was the taxonomy

Let us give credit when credit is due. The original concept of ‘variety‘ has been established by the taxonomists. Taxonomy is “the science of naming, identifying and classifying living organisms”, as reminded by Kew Gardens (UK) Accelerated Taxonomy department.

Taxonomists refer to the “International code of Botanical Nomenclature” that has now become the “International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi and plants” produced by the “International Association for Plant Taxonomy” (IAPT). As per this code (see Article 4 & 26), variety (or the Latin varietas) is a rank of taxon below species. The description of a variety is based solely on a botanical description.

Then, taxonomists acknowledged that cultivated plant variants, below the rank of species, had a specific status. Hence, the “International Society for Horticultural Science” (ISH) produced in 1953 the first edition of “International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants” (ICNCP), focusing on the cultivated varieties or cultivars = “The basic independent category used for agriculture, forestry and horticulture (…)”. The ninth (most recent edition) was published in 2016. The precise definition of a cultivar is given in Article 2.3 of ICNCP:

“A cultivar, as a taxon, is an assemblage of plants that (a) has been selected for a particular character or combination of characters, (b) is distinct, uniform, and stable in these characters, and (c) when propagated by appropriate means, retains those characters”

Then came the breeders and breeders’ rights

The ‘variety’ according to UPOV

In 1961, the “International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants” (UPOV) was created and the UPOV convention was produced to provide a legal framework for the protection of ‘varieties’ and breeders’ right. It seems as if UPOV ignored the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants. Indeed, UPOV used the word ‘variety’ in the sense of taxonomists’ ‘cultivar’. This has been the source of all the confusion. Why UPOV didn’t use the relevant term ‘cultivar’? I really don’t know, but as a breeder, I think they should have.

The definition by UPOV of a variety is given in Article 1 (vi) of the 1991 Act of the UPOV Convention and is reproduced below :

“Variety” means a plant grouping within a single botanical taxon of the lowest known rank, which grouping, irrespective of whether the conditions for the grant of a breeder’s right are fully met, can be:

- Defined by the expression of the characteristics resulting from a given genotype of combination of genotypes

- Distinguished from any other plant grouping by the expression of at leas one of said characteristics and

- Considered as a unit with regard to its suitability for being propagated unchanged

It is indeed similar to the ‘cultivar’ previously defined by taxonomists.

Definition of a variety that can be granted a Breeder’s right (ICPNVP / UPOV)

Article 5 of the UPOV convention states that the criteria to be satisfied for a Breeder’s right to be granted for a given variety are: New, Distinct, Uniform and Stable.

Hence, for UPOV, the difference between a variety and a variety eligible to a breeder’s right is that the later should be new.

New, as per UPOV definition (Article 6), means that the variety should not have been commercialized at the time of applying for a breeder’s right.

UPOV also recognized that the new variety shall be “clearly distinct from any other variety whose existence is a matter of common knowledge at the time of the filing of the application”

For instance, the coffee “Bourbon” is a cultivar = variety as per the UPOV definition but it is not eligible to breeder’s right because its existence is a matter of common knowledge.

Definition of a landrace

There is no official acknowledge definition of a landrace. However, the concept has been discussed at length, namely by Zeven in 1998, and Casañas et al in 2017. We find that the easiest, yet valid, definition is given by Casañas et al in 2017 in their abstract:

“The term ‘landrace’ has generally been defined as a cultivated, genetically heterogeneous variety that has evolved in a certain ecogeographical area and is therefore adapted to the edaphic and climatic conditions and to its traditional management and uses. Despite being considered by many to be inalterable, landraces have been and are in a constant state of evolution as a result of natural and artificial selection”.

Definition of heirloom

The etymology of Heirloom is a ‘tool’ that is inherited (‘heir’) from ancestors. There is no major difference between heirloom and landraces.

Note on varietals:

“Varietal” is a word coming from the Anglo-Saxon wine industry refereeing to the wine coming from one single variety. It is sometimes used in the coffee industry but unfortunately often using varietal as a synonymous of variety, which is not correct.

Note on the concept of accession

You might have heard or read the term ‘accession’. Let’s read the definition by the US National Plant Germplasm System : “An accession is a distinct, uniquely identified sample of seeds or plants, that is maintained as part of a germplasm collection.”

An accession is hence related to germplasm (= genetic resources) collection. It can represent a variety, a cultivated variety (= cultivar), a sample of a landrace or a sample of wild populations.

Examples of cultivars in coffee

Examples of cultivars = breeders’ varieties:

- Non eligible for breeder’s right (ancient common knowledge): Bourbon, Typica, Caturra, Geisha…

- Eligible for Breeder’s rights: Obata, Catigua, Ruiru 11, Batian, Marsellesa, Starmaya…

Examples of Landraces :

- Most cultivated robusta coffee ( canephora) in Africa.

- Most cultivated Arabica coffee in Ethiopia (apart from cultivars selected by research), in South Sudan and in Yemen.

- Outside of Ethiopia and Yemen, I would argue that the Timor Hybrid population in East Timor is a landrace.